The Brain’s Amazing Capacity for Memory: A Comprehensive Review of Research Findings

From Perception to Action: The Intricacies of Memory and How It Shapes Our Lives

From Perception to Action: The Intricacies of Memory and How It Shapes Our Lives

Welcome to my article on memory! As someone who often forgets where they left their keys or parked their car, I’ve always been fascinated by the mysteries of human memory. In this article, I am going to take you on a journey through the different types of memory, the processes involved in encoding and retrieving information, and the many fascinating things that scientists have learned about how our brains remember. I have been following the psychological research on this topic for a long time and it never ceases to amaze me.

Memory refers to the mental processes involved in encoding, storing, and retrieving information. Put simply, it’s how our brains remember things. There are many different types of memory, each with its own unique characteristics and processes. In this article I am planning to explore these different types of memory and also multiple different ways our memory affect our existence. My goal is to share my readings and understanding of this topic with you.

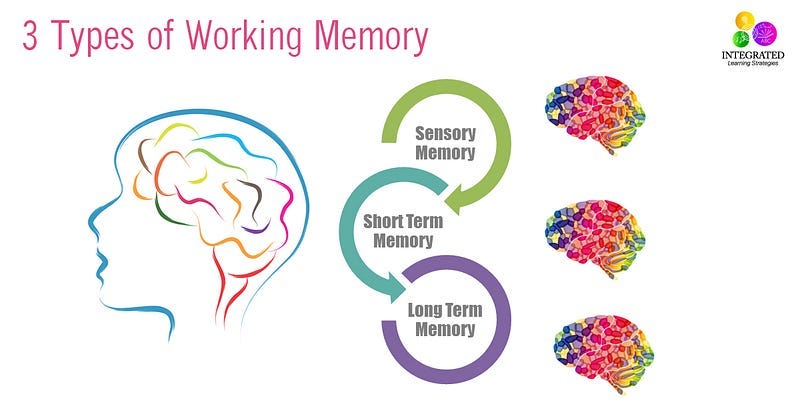

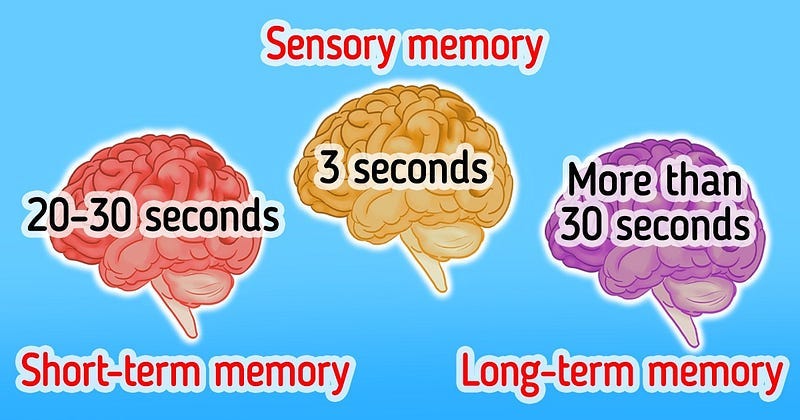

Sensory Memory

It’s the initial processing of sensory information from the environment. As I said before, it is like a brief snapshot of the world around us, holding onto information for just a few seconds before it fades away.

So, how does sensory memory work? Let’s say you’re looking at a beautiful sunset. Your eyes take in the visual information — the colors, the shapes, the movement of the clouds — and send it to your brain for processing. This information is held in sensory memory for just a few seconds before it’s either forgotten or transferred to short-term memory.

Sensory memory is divided into different modalities based on the sensory system involved. For example, iconic memory refers to the brief storage of visual information, while echoic memory refers to the brief storage of auditory information. Other modalities include haptic memory (touch), olfactory memory (smell), and gustatory memory (taste).

One interesting thing about this memory is that it’s automatic — we don’t have to consciously try to remember sensory information, it just happens. However, its capacity is limited, and we can only hold onto a certain amount of information for a short period of time. This is why sensory memory is sometimes called “buffer memory” — it acts as a buffer between the environment and our conscious awareness, holding onto information briefly before deciding whether to transfer it to short-term memory or let it fade away.

Scientists have used a variety of experimental methods to study it, including the partial-report technique and the whole-report technique. These methods involve presenting participants with stimuli (e.g., letters or numbers) and measuring their ability to recall them after a brief delay. These experiments have provided insights into the capacity, duration, and modality-specificity of sensory memory.

Short-term Memory

Short-term memory is like a temporary storage space for information that we need to hold onto for a short period of time — think of it like a mental “sticky note” that helps us remember things in the moment.

So, how does short-term memory work? Let’s say you’re trying to remember a phone number that someone just told you. You repeat the numbers to yourself over and over again in your head — this is known as rehearsal — in order to keep them in short-term memory. However, if you’re distracted or if too much time passes, the phone number will likely be forgotten.

It also has a limited capacity. The exact capacity of this memory is still a topic of debate among scientists, but it’s generally thought to be around 7 items, plus or minus 2. So, if you’re trying to remember a phone number that’s 10 digits long, you may need to break it up into smaller chunks in order to hold onto it in short-term memory.

One model of short-term memory is Baddeley’s model of working memory. According to this model, short-term memory is composed of three components: the phonological loop, the visuospatial sketchpad, and the central executive. The phonological loop is responsible for holding onto verbal information (like the phone number example), while the visuospatial sketchpad is responsible for holding onto visual information. The central executive is like the boss of the whole system, directing attention and coordinating information between the two slave systems.

This memory is easily disrupted by interference or distraction. For example, if you’re trying to remember a list of words and someone starts talking to you, your short-term memory for the words may be disrupted. However, some strategies can be used to improve short-term memory, such as chunking (grouping information together) and elaborative rehearsal (connecting new information to existing knowledge).

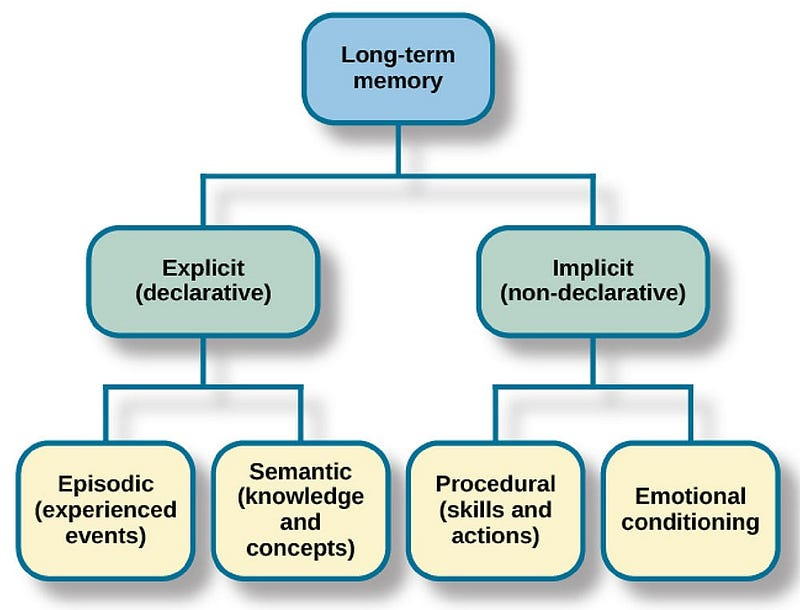

Long-term Memory

Long-term memory is where our brains store information for a much longer period of time — from several minutes to a lifetime.

The process of long-term memory involves three stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. Encoding is the process of taking in information and turning it into a form that can be stored in long-term memory. Storage is the process of maintaining the encoded information over time. Retrieval is the process of accessing stored information when needed.

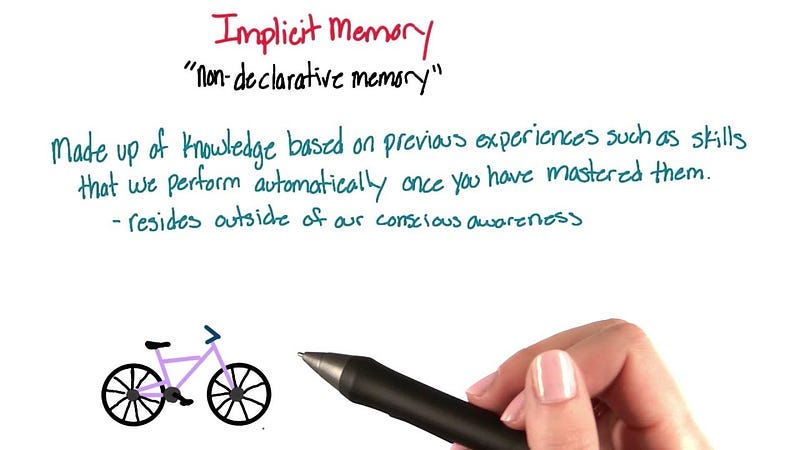

It is also further divided into two types: explicit (declarative) memory and implicit (procedural) memory. Explicit memory is the conscious and intentional recall of past events, experiences, and knowledge. Explicit memory can be further divided into two subtypes: episodic memory and semantic memory. Episodic memory refers to the memory of personal experiences and events, while semantic memory refers to the memory of general knowledge and facts.

Implicit memory is the unconscious and unintentional recall of past events, experiences, and knowledge. Implicit memory is involved in the learning and retention of skills, habits, and behaviors. It is often difficult to put into words and is demonstrated through performance or behavior. Examples of implicit memory include riding a bike or playing a musical instrument.

The neural mechanisms and brain regions involved in long-term memory are complex and still not fully understood. However, it’s known that the hippocampus plays a critical role in the formation of new long-term memories. The hippocampus is involved in the encoding and retrieval of episodic memories, as well as the consolidation of memories from short-term to long-term storage.

Factors that affect long-term memory include emotional arousal, context effects, and repetition. For example, memories that are emotionally arousing (such as a traumatic event) are more likely to be remembered than neutral events. Context effects refer to the idea that the context in which information is learned can affect how well it’s remembered later. And repetition is an important factor in encoding information into long-term memory — the more times information is repeated, the more likely it is to be remembered.

Explicit (Declarative) Memory

Explicit memory is essential for our daily lives, allowing us to remember important events, learn new skills and knowledge, and navigate the world around us. Now, let’s see how it works. Let’s say you’re trying to remember a conversation you had with a friend yesterday. This is an example of episodic memory — the memory of personal experiences and events. It is thought to be encoded and stored in the hippocampus, a brain region that’s critical for memory formation.

Semantic memory, on the other hand, refers to the memory of general knowledge and facts. For example, remembering that Paris is the capital of France is an example of semantic memory. It is thought to be encoded and stored in the neocortex, a brain region that’s involved in higher-order cognitive processes.

Assessment and measurement of explicit memory can be done in various ways, such as recall, recognition, and relearning. Recall involves retrieving information from memory without any cues or prompts. For example, trying to remember the name of your high school teacher without any hints. Recognition involves identifying previously learned information from a list of options. For example, recognizing your high school teacher’s name from a list of names. Relearning involves relearning previously learned information that has been forgotten. For example, relearning a language that you learned in school but haven’t used in years.

Implicit (Procedural) Memory

As described before, this memory is involved in the learning and retention of skills, habits, and behaviors. The way it works is like let’s say you’re learning how to ride a bike; at first, you need to consciously think about each step — how to balance, pedal, and steer. However, with practice, these actions become automatic and unconscious — you no longer need to think about each step, you just do it.

This memory is thought to be encoded and stored in various brain regions, including the basal ganglia and cerebellum. The basal ganglia is involved in the formation and retention of motor and procedural memories, while the cerebellum is involved in the coordination and timing of movements.

Assessment and measurement of this memory can be done in various ways, such as reaction time and the implicit association test (IAT). Reaction time involves measuring the time it takes to perform a task, such as pressing a button in response to a stimulus. The IAT involves measuring the speed with which participants associate certain concepts (e.g., “good” or “bad”) with certain groups of stimuli (e.g., names of different races).

Factors that affect implicit memory include repetition, task complexity, and transfer effects. I explained repetition before, it is an important factor in the learning and retention of skills and habits. Task complexity refers to the level of difficulty of a task — more complex tasks may require more explicit memory processes before becoming implicit. Transfer effects refer to the idea that skills learned in one context may not transfer to a different context, highlighting the importance of practicing skills in a variety of situations.

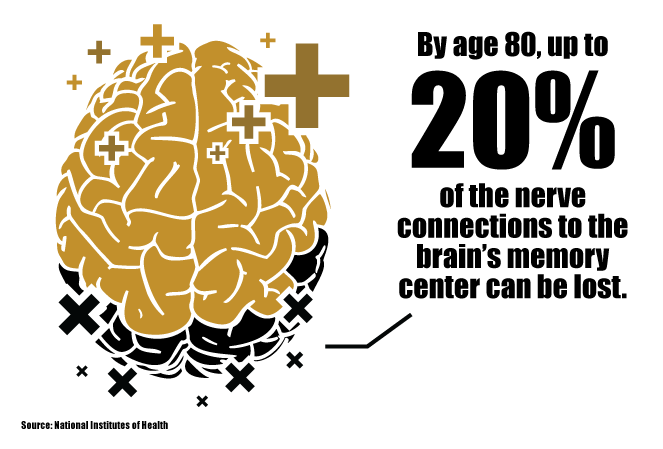

Memory and Aging: A Journey Through the Golden Years

As we grow older, we accumulate countless memories and experiences. Some of them remain vivid and clear, while others seem to drift away like wisps of fog. Aging is a natural part of life, and with it comes changes in our memory processes. Now, it’s important to remind that age-related memory decline is completely normal. As we age, certain cognitive functions, including memory, may experience a decline in efficiency. You may find that it takes a little longer to recall things.

However, it’s crucial to differentiate between normal age-related memory decline and pathological memory loss, such as dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. While typical memory decline may cause minor inconveniences, pathological one is a more severe and debilitating condition that requires medical attention.

What causes these changes in memory as we age? Well, there are several factors at play. For one, age-related changes in the brain, such as a decrease in brain volume and a reduction in neurotransmitter production, can impact memory processes. Moreover, factors like chronic stress, poor sleep, and an unhealthy lifestyle can also contribute to memory decline.

Firstly, it’s essential to stay mentally active. Just as our bodies need physical exercise, our brains need a good workout too! Engage in mentally stimulating activities like crossword puzzles, Sudoku, or learning a new language. These activities help maintain cognitive abilities and may even help build new neural connections.

Secondly, social engagement is key. Spending time with friends, joining clubs or community groups, and participating in social events can boost our mood and keep our minds sharp. Plus, who doesn’t love a good get-together?

Thirdly, a healthy lifestyle can work wonders for our memory. Make sure to eat a balanced diet filled with brain-boosting nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and vitamins. Don’t forget to get regular exercise, as physical activity has been shown to improve brain health and reduce the risk of cognitive decline. And, of course, prioritize a good night’s sleep — it’s essential for memory consolidation and overall well-being.

Strategies for Memory Improvement

Let’s explore various strategies and techniques that can help you improve your memory and recall information more effectively. The good news is that our memory is not set in stone, and with a little effort and some fun tricks, you can give it a boost!

Mnemonic Devices: These memory aids help you encode information in a more memorable way, making it easier to retrieve later. For example, you might use acronyms (e.g., HOMES to remember the Great Lakes: Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior) or rhymes (e.g., “Thirty days hath September, April, June, and November…”) to assist in recalling specific details.

Method of Loci (Memory Palace): This ancient technique involves associating information with specific locations in a familiar environment. To use this method, imagine yourself walking through a familiar place, like your home, and mentally “placing” items or concepts you want to remember at various points along the way. When you need to recall the information, simply take a mental walk through the same environment and “pick up” the items as you go.

Spaced Repetition: Research has shown that spacing out your learning sessions over time helps improve long-term memory retention. Instead of cramming information all at once, try reviewing it in small, focused sessions, spaced over a few days or weeks. This allows your brain to consolidate the information more effectively, making it easier to recall later on.

Active Recall: Instead of passively reading or listening to information, engage with it actively by testing yourself. For example, try to recite key points from memory, quiz yourself with flashcards, or explain the concepts to someone else. Active recall strengthens the memory traces and helps consolidate the information in long-term memory.

Visualization: Creating vivid mental images can help make abstract information more concrete and memorable. For instance, when trying to remember a new word or concept, visualize a scene or image that represents it. The more detailed and vivid your mental image, the more likely you are to remember the information.

Elaborative Rehearsal: Rather than simply repeating information, connect it to something you already know. By associating new information with existing knowledge, you create more retrieval cues, making it easier to recall the information later. For example, when learning a new vocabulary word, think of a sentence that uses the word and relates to your own experiences.

Chunking: Breaking down large amounts of information into smaller, more manageable chunks can help improve short-term memory capacity. For example, when trying to remember a 10-digit phone number, break it into smaller groups (e.g., 555–123–4567) to make it easier to remember.

Healthy Habits: Maintaining a healthy lifestyle can have a positive impact on memory. Proper nutrition, regular exercise, and adequate sleep are all essential for optimal brain functioning. Consuming foods rich in antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids, engaging in physical activities that get your heart pumping, and ensuring you get enough quality sleep can all contribute to better memory performance.

Mindfulness and Meditation: Practicing mindfulness and meditation has been shown to help improve attention and focus, which can, in turn, enhance memory. By regularly engaging in mindfulness exercises, such as deep breathing or body scans, you can train your brain to be more present and better able to absorb new information.

Stay Curious and Engaged: Finally, keep your mind active and engaged by continuously learning and challenging yourself. Pursue new hobbies, solve puzzles, read widely, and engage in social activities. These cognitive exercises can help keep your memory sharp.

The Role of Emotions in Memory

It’s no secret that emotions play a significant role in our lives, from the warm fuzzies we get when reuniting with a long-lost friend to the heart-wrenching sadness that comes with a breakup. But have you ever wondered how emotions can impact our ability to remember certain events?

First, let’s talk about the basics. Emotions can act like a highlighter pen for our memories, making some events stand out in vivid detail while others fade into the background. Studies have shown that emotionally charged events are often remembered better than neutral events. For example, you might not recall what you had for breakfast last Tuesday, but you’ll likely remember the joy of receiving a surprise birthday party or the shock of hearing unexpected bad news.

The reason behind this emotional memory boost lies in the power of our brain’s very own drama queen: the amygdala. The amygdala is a small, almond-shaped structure nestled deep within the brain that plays a crucial role in processing emotions. When we experience an emotionally charged event, the amygdala springs into action, signaling to other brain areas (including the hippocampus, our memory superstar) that this event is important and should be prioritized in memory storage.

Now, you might be thinking, “Great! So, all my emotional memories will be crystal clear, right?” Well, not so fast. While it’s true that emotional memories are generally better remembered, they can also be prone to distortion. In other words, our emotional memories can be as melodramatic as a soap opera, sometimes bending the truth to fit the narrative.

Take, for instance, the phenomenon of flashbulb memories. These are highly detailed, exceptionally vivid memories of shocking or emotionally charged events, like hearing about a major news event or experiencing a personal tragedy. While people often report great confidence in the accuracy of their flashbulb memories, research has shown that these memories can be just as susceptible to distortion and forgetting as more mundane memories.

So, why does this happen? One possible explanation is that our emotional state at the time of an event can influence how we encode and later retrieve that memory. High levels of stress or anxiety during an event, for example, can narrow our focus and cause us to remember only certain aspects of the situation, potentially leading to memory distortions. Additionally, our current emotional state can also color our memories, sometimes causing us to remember past events in a more positive or negative light than they actually were.

Understanding the impact of emotions on memory can actually help us harness their power for good. For example, teachers and educators can use emotionally engaging materials or storytelling techniques to enhance students’ memory and learning. And on a personal level, we can use positive emotions to improve our own memory by associating new information with pleasant experiences or engaging in activities that elicit positive emotions, such as listening to music or spending time with loved ones.

So, the next time you find yourself on the emotional roller coaster of life, remember that your emotions have the power to shape your memories in fascinating ways. And while emotional memories might not always be the most accurate, they’re certainly some of the most memorable!

Memory and Sleep

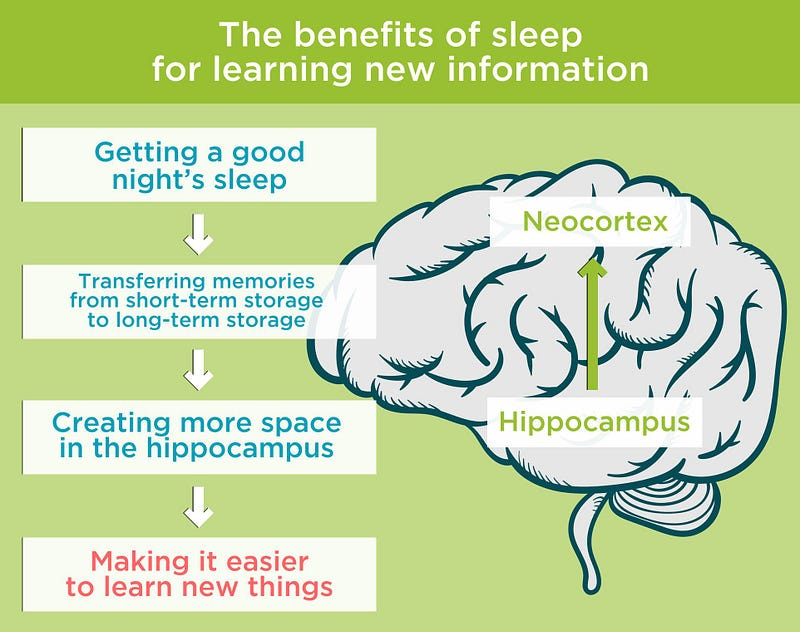

Now let’s explore how catching some Z’s can make a real difference to our memory. Sleep is more than just a time for our bodies to recharge; it’s actually a critical period for our brains to process and consolidate the information we’ve learned during the day. As we drift off into dreamland, our minds are hard at work, connecting the dots between new experiences and existing knowledge. In fact, sleep plays such a vital role in memory that trying to remember something after a poor night’s sleep can feel like searching for your keys in the dark — frustrating and fruitless.

Now, let’s dive a little deeper into the various stages of sleep and how they affect memory. Sleep can be divided into two main categories: rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. NREM sleep consists of three stages (N1, N2, and N3), which gradually progress from light sleep to deep sleep. REM sleep, on the other hand, is the stage when we typically experience vivid dreams and is characterized by rapid eye movements and increased brain activity.

Here’s where it gets interesting: both REM and NREM sleep have been shown to play distinct roles in memory consolidation. During the deep sleep stages of NREM (particularly N3), our brains primarily work on consolidating declarative memories — those memories of facts, events, and experiences that we can consciously recall. During this time, the hippocampus, that memory maestro in our brains, replays neural activity patterns from the day, helping to strengthen connections between neurons and transfer information to the neocortex for long-term storage.

Meanwhile, REM sleep is thought to be more involved in consolidating procedural and emotional memories. During REM sleep, our brains integrate new procedural skills and emotional experiences with existing knowledge, which helps us better adapt to new situations and learn from past experiences.

But what happens when our sleep quality takes a nosedive? Well, research has shown that sleep deprivation can wreak havoc on our memory. Poor sleep can lead to difficulties in encoding new information, consolidating memories, and retrieving information when needed. In other words, without enough shut-eye, we may struggle to remember important details, learn new skills, or even recall the name of that catchy tune we heard on the radio.

So, if you want to give your memory a fighting chance, make sure to prioritize quality sleep. Stick to a consistent sleep schedule, create a relaxing bedtime routine, and ensure your sleep environment is conducive to a good night’s rest. After all, a well-rested brain is a remembering brain, ready to tackle the day’s challenges and create memories that will last a lifetime.

Neuroplasticity and Memory

Neuroplasticity refers to your brain’s capacity to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. It’s like your brain’s very own shape-shifter, continually adapting to new experiences and challenges.

Memory and neuroplasticity go together like peanut butter and jelly. When we learn something new or create a memory, our brain changes by forming new connections between neurons, the brain’s superstar cells. These connections, known as synapses, help transfer information within the brain, allowing us to store and retrieve memories like a well-oiled machine.

You may have heard the saying, “Use it or lose it.” Well, it turns out that this phrase applies to your brain too! When you actively engage in learning new skills or information, you’re essentially giving your brain a workout, which helps keep it in tip-top shape. Research has shown that stimulating mental activities can lead to improved memory and cognitive function, thanks to our brain’s neuroplastic abilities. In other words, keeping your brain challenged is like sending it to the gym — the more you exercise it, the stronger it becomes.

But how can you harness the power of neuroplasticity to boost your memory? Let me share a few tips that are bound to make your brain feel like it’s flexing its muscles:

Embrace novelty: Tickle your brain cells by trying out new activities or learning new skills. Whether it’s mastering the art of knitting or learning to play the ukulele, exposing your brain to new experiences helps promote neuroplasticity and strengthens memory.

Challenge yourself: Don’t be afraid to push your limits! Engaging in tasks that are slightly out of your comfort zone encourages your brain to adapt and form new connections. Sudoku, crossword puzzles, or learning a new language — the possibilities are endless!

Stay socially active: Social interaction is not only great for your emotional well-being but also beneficial for your brain. Engaging in stimulating conversations with others can help keep your mind sharp and encourage neuroplasticity.

Meditate: Meditation has been shown to have numerous benefits for the brain, including promoting neuroplasticity. Regular practice can help improve focus, reduce stress, and boost memory.

Get moving: Physical exercise is not only good for your body, but it’s also fantastic for your brain. Research has shown that regular aerobic exercise can increase the size of the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for memory and learning.

Memory in the Digital Age: A Double-Edged Sword?

In today’s fast-paced digital world, our gadgets and devices have become an integral part of our lives. From smartphones to laptops, we’re constantly connected and rely on technology for everything, including storing and retrieving information. But have you ever stopped to wonder how this reliance on technology might be affecting our memory?

First, let’s talk about the “Google effect.” Coined by researchers Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Liu, and Daniel M. Wegner, the term refers to our tendency to forget information that can be easily found using search engines like Google. This effect is based on the concept of transactive memory, where we rely on external sources, such as friends, spousses, family, or in this case, the internet, to store and retrieve information for us. In a way, the internet has become our collective external hard drive!

Now, is this a bad thing? Not necessarily. The Google effect can free up our cognitive resources, allowing us to focus on more complex tasks or creative problem-solving instead of trying to remember every single detail. Plus, having instant access to vast amounts of information can help us learn new things, stay informed, and make better decisions. It’s quite remarkable that we can have the entire world’s knowledge at our fingertips!

However, there’s a flip side to this coin. Relying too heavily on digital devices for information storage and retrieval might make our memory skills a little rusty. For instance, how many phone numbers do you actually remember these days? It seems that our devices are so good at remembering things for us that we’re becoming a little too complacent.

Furthermore, our constant exposure to technology and the internet can also lead to information overload. With so much data being thrown at us every day, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to filter out the relevant information and commit it to memory. As a result, we might find it challenging to remember important details or struggle with retaining new information in the long run.

So, what can we do to strike a balance? Here are a few tips for maintaining healthy memory habits in the digital age:

Be mindful of your tech usage: Try to find a balance between relying on technology for information and using your own memory skills. Use technology as a tool to enhance your memory, not as a crutch.

Practice active reading: When you come across interesting or important information online, don’t just skim through it. Read actively, engage with the material, and try to connect it to your existing knowledge to help it stick in your memory.

Test your memory: Challenge yourself to recall phone numbers, addresses, or other important details without looking them up. This will help keep your memory skills sharp.

Take breaks from screens: Give your brain some time to rest and recharge by taking regular breaks from screens. This can help reduce information overload and improve focus and concentration.

Engage in memory-boosting activities: Participate in activities that are known to enhance memory, such as physical exercise, meditation, or playing memory games.

Cultural and Social Aspects of Memory

Memory isn’t just an individual cognitive process — it’s also deeply intertwined with our cultural and social experiences. Our memories are, in many ways, shaped by the world we live in and the people we interact with.

Collective Memory: Remembering as a Group

Collective memory refers to the shared remembrance of events, experiences, and knowledge within a social group. It plays a vital role in preserving and transmitting cultural heritage, shaping our understanding of history, and fostering a sense of shared identity.

One fascinating example of collective memory is the way societies remember and commemorate significant historical events, such as national holidays or memorial ceremonies. These collective rituals serve to reinforce the group’s shared understanding of the past and, in turn, shape the collective memory of future generations.

Cultural Transmission: Passing on the Baton of Memory

It is the process through which knowledge, beliefs, and customs are passed down from one generation to another. Memory plays a crucial role in this process, as individuals must remember and share cultural information with others in their community. From teaching youngsters the family recipes to passing down folktales and traditional dances, cultural transmission relies on the ability of our memories to store and convey this wealth of information.

The Role of Language and Narratives in Memory

Language is an essential tool in the formation and expression of memories. It allows us to communicate our experiences and knowledge with others, weaving individual memories into shared narratives. Moreover, the way we narrate our experiences can shape the way we remember them. For example, cultural differences in storytelling can influence memory organization and retrieval. Some cultures might prioritize chronological order in recounting experiences, while others may place greater emphasis on the emotional impact or moral lessons.

Social Influences on Memory: Friends, Family, and Frenemies

Our social environment can have a significant impact on memory formation and recall. For example, we might be more likely to remember events that were emotionally charged or socially meaningful, such as a heartwarming conversation with a loved one or an awkward encounter with an ex. In addition, the social context in which information is learned can affect how well it’s remembered later. For instance, you might be more likely to remember a joke that had everyone laughing at a party than a random fact you read online.

Moreover, social influences can sometimes lead to memory distortions, as we are susceptible to incorporating others’ suggestions or beliefs into our own memories. This phenomenon, known as “memory conformity” or the “social contagion of memory,” can lead to the creation of false memories or altered recollections of events.

Memory and Learning

Picture this: you’re learning a new language, maybe Italian, because who wouldn’t want to stroll down the streets of Milan speaking like a true Italian? In order to master this lovely language, you’ll need to rely on your memory to store and retrieve all those new vocabulary words and grammar rules. Without memory, you’d be stuck relearning the same words and phrases over and over again (cue “Groundhog Day” vibes).

Now, let’s talk about different types of learning. There’s explicit learning, where you’re consciously aware of the information you’re trying to learn, like when you practice those Italian verb conjugations. On the other hand, there’s implicit learning, which occurs without you even realizing it. For instance, you might unconsciously pick up on the rhythm and intonation of spoken Italian just by listening to native speakers. Both types of learning rely heavily on our memory systems, with explicit learning tapping into our good friends, explicit (declarative) memory, and implicit learning being all chummy with implicit (procedural) memory.

Have you ever heard of the “testing effect” or “retrieval practice”? This nifty learning strategy involves actively recalling information from memory, rather than simply rereading or passively reviewing the material. Studies show that this approach actually strengthens memory, making it easier to remember what you’ve learned in the long run. So, next time you’re studying for a big exam or trying to memorize a recipe, quiz yourself to give your memory a workout!

Another fun learning technique that benefits memory is “interleaving.” Instead of focusing on one topic or skill at a time, you mix things up and alternate between different subjects or tasks. This approach can improve memory retention and help you transfer learned skills to new situations. So, if you’re learning Italian and, let’s say, playing the ukulele, you could practice conjugating verbs for 20 minutes, then strum a few chords, and then go back to practicing more verbs.

In conclusion, memory and learning are a dynamic duo, constantly supporting and reinforcing each other. They work together like a well-choreographed dance, allowing us to acquire new knowledge, skills, and experiences.

False Memories and Memory Distortions

You might think that our memories are like a trusty video recorder, capturing events exactly as they happened. However, our brains can sometimes play tricks on us, creating memories that seem real but are actually figments of our imagination or distorted versions of what really happened. Spooky, isn’t it?

False memories are memories of events or experiences that never actually occurred, but are believed to be true by the person recalling them. Memory distortions, on the other hand, involve recalling real events, but with alterations or inaccuracies. Both can be influenced by various factors, such as suggestion, leading questions, or even the mere passage of time.

A famous example of how false memories can be implanted is the “Lost in the Mall” study by Elizabeth Loftus, a renowned memory researcher. In this study, participants were presented with a series of stories about their childhood, some of which were true and some fabricated. One of the false stories involved the participant getting lost in a shopping mall as a child. Surprisingly, many participants not only believed this false story but also added their own vivid details, further reinforcing the false memory. This study demonstrates the malleability of memory and how easily our brains can be persuaded to believe in events that never happened.

Another intriguing example is the “misinformation effect,” which occurs when people’s memories are influenced by incorrect or misleading information provided after the event. Imagine you witnessed a car accident and later discussed it with a friend who mentioned a stop sign at the scene. If there was no stop sign present, but you later recall seeing one, you’ve experienced the misinformation effect. This phenomenon has important implications, especially in the context of eyewitness testimony, where the accuracy of memories can be crucial in legal cases.

Now, you might be wondering, why do false memories and memory distortions occur? Researchers believe that one reason is our brain’s tendency to fill in gaps in our memory with plausible, but not necessarily accurate, information. This “memory reconstruction” helps us make sense of our experiences, but can also lead to errors. Furthermore, our memories can be influenced by social pressure, expectations, and even our current emotional state.

To minimize the chances of creating false memories or distorting real ones, it’s essential to be aware of these memory pitfalls. When recalling events, try to avoid external influences, such as leading questions or suggestive comments.

Case Studies and Famous Memory Experiments

Memory has always been a fascinating topic for psychologists, neuroscientists, and everyday people like you and me. Many intriguing experiments have been conducted over the years to shed light on how our memories work, and the results have often been surprising. Let’s dive into some of the most famous and influential memory experiments and case studies.

The H.M. Case Study: Who could forget the case of Henry Molaison, or H.M., as he is affectionately known? After a surgery to treat his epilepsy, H.M. lost the ability to form new long-term memories. This led to groundbreaking insights into the role of the hippocampus in memory formation. H.M.’s unique condition reminded us that our memories are precious, and perhaps a little fragile, too.

The Atkinson-Shiffrin Model: Remember that time when Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin gave us the multi-store model of memory in 1968? They proposed that our memories are formed through a series of stages: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. This model has been hugely influential, even though some aspects have been revised over time.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve: Hermann Ebbinghaus was a real trailblazer when it came to studying memory. His forgetting curve demonstrated that our ability to retain information diminishes rapidly over time, particularly if we don’t make a conscious effort to review it. The lesson here? Keep practicing and revisiting information if you want to keep it fresh in your mind!

The Loftus and Palmer Car Crash Study: In this classic experiment, Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer set out to show just how easily our memories can be manipulated. They asked participants to estimate the speed of cars involved in a crash, but subtly changed the wording of the question. Turns out, our memories are quite malleable .

The Serial Position Effect: Ever noticed that you tend to remember the first and last items in a list more easily than the ones in the middle? This phenomenon, known as the serial position effect, was first observed by Hermann Ebbinghaus (yes, him again!). It’s a handy little trick to remember when you’re trying to memorize the grocery list.

The Baker/baker Paradox: Here’s a fun one: participants in a study were shown a picture of a man and told either that his last name was Baker or that he was a baker by profession. Later on, people were better at remembering the profession than the name. This experiment highlights the power of context and associations in memory formation.

The Method of Loci: This ancient memory technique has stood the test of time, dating all the way back to the ancient Greeks. By mentally “placing” items to remember along a familiar route or location, individuals can more easily recall them later. It’s like a mental treasure hunt, and who doesn’t love a good treasure hunt?

The McGurk Effect: In this fascinating experiment, participants watched a video where the audio and visual components were mismatched. The result? They “heard” a sound that was a blend of the two! This demonstrated that our memories are not just based on a single sense but are instead an integration of all our sensory experiences.

The Mandela Effect: Named after the mistaken belief that Nelson Mandela died in prison in the 1980s, the Mandela Effect refers to instances where a large group of people collectively “misremember” an event or fact. This phenomenon highlights the fallibility of our memories and the role that social influences can play in shaping them. It’s a fascinating reminder that sometimes, our memories can be this unreliable.

Future of Memory Research

Memory research has made significant strides in recent years, providing us with new insights into how memory works and how we can improve it.

One area of research is memory enhancement. Scientists are exploring various methods for enhancing memory, such as brain training exercises, cognitive therapy, and medication. For example, some studies have shown that aerobic exercise can improve memory in older adults. Other studies have explored the use of cognitive enhancers, such as modafinil and methylphenidate, in improving memory and cognitive functioning in healthy individuals.

Another area of research is memory rehab . It involves using various strategies and techniques to improve memory functioning in individuals with memory impairments, such as those with Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injury. Some of these strategies include memory aids (such as calendars and reminder apps), cognitive rehab therapy, and memory training exercises.

Memory research has also provided us with new insights into memory disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and amnesia. For example, researchers have identified the role of beta-amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. They have also identified various risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, such as genetics and lifestyle factors.

Other areas of memory research include the effects of sleep on memory consolidation, the role of emotions in memory formation and retrieval, and the impact of stress on memory functioning. Scientists are also exploring the use of brain imaging techniques, such as fMRI and PET scan, in studying the neural mechanisms of memory.

Conclusion

Human memory is an intricate and multifaceted cognitive process that enables us to encode, store, and retrieve information. In this article, I tried to take you a journey through the various types of memory, from sensory to short-term to long-term, and explore the distinctions between explicit and implicit memories.

By shedding light on the neural mechanisms and factors that influence memory, as well as current and future research in memory enhancement and rehabilitation, I tried to provide you with a deeper understanding of the marvels of human memory.

As memory research continues to evolve, we can anticipate new discoveries and advances that will further enrich our understanding of this essential cognitive function and help us improve our own memory capabilities in everyday life.

More References for studying Psychology

The Mental Tug-of-War: A Study of Cognitive Dissonance and its Consequences (link)

Mind Over Matter: The Science Behind Availability Heuristic in Everyday Life (link)

Beyond Self-Delusion: The Science of Illusory Superiority (link)

Uncovering the Roots of Self-Serving Bias (link)

The Dark Side of Attribution: How Our Perceptions Can Impact Relationships and Decisions (link)

Following The Crowd: The Psychology Of The Bandwagon Effect (link)

Perception, Interpretation, and Bias: Examining Actor-Observer Dynamics (link)

The Impact of Negativity Bias on Mood, Decision Making, and Relationships (link)

Hindsight Bias: Understanding the Psychology Behind Our 20/20 Vision (link)

How to Win Friends and Influence People: The Ben Franklin Effect (link)

From Pessimism to Paralysis: The Role of ‘Declinism’ in Shaping Our Social and Political Reality (link)

The High Cost of Naive Cynicism: How Pessimism and Distrust Hold Us Back (link)

How to Win Friends and Influence People: The Ben Franklin Effect (link)

The Genetics and Neuroscience of General Intelligence: Implications for Education and Society (link)

The Illusion of Consensus: Understanding the False Consensus Effect (link)

Unpacking Social Loafing: The Role of Group Composition and Task Characteristics (link)

The Power and Perils of Gaslighting: Understanding and Overcoming Psychological Manipulation (link)

I hope you enjoyed reading this 🙂. If you’d like to support me as a writer consider signing up to become a Medium member. It’s just $5 a month and you get unlimited access to Medium 🙏 .

Before leaving this page, I appreciate if you follow me on Medium and Linkedin 👉

Also, if you are a medium writer yourself, you can join my Linkedin group. In that group, I share curated articles about data and technology. You can find it: Linkedin Group. Also, if you like to collaborate, please join me as a group admin.